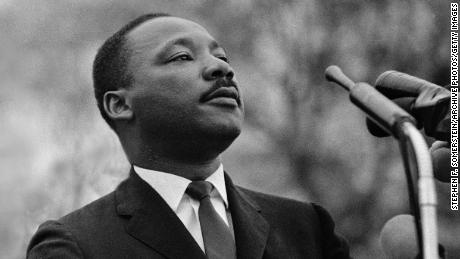

“Let us all hope that the dark clouds of racial prejudice will soon pass away and the deep fog of misunderstanding will be lifted from our fear-drenched communities and in some not too distant tomorrow the radiant stars of love and brotherhood will shine over our great nation with all their scintillating beauty.

Yours in the cause of Peace and Brotherhood,

Martin Luther King Jr.”

So concluded Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham City Jail”, penned in a jail cell in April of 1963 where King had been incarcerated for his participation in the Birmingham civil rights demonstrations. The letter is an appeal to the so-called “white moderate” Alabama religious leaders to see, among other things, that the struggle for civil rights could not wait, that injustice anywhere was a threat to justice everywhere, that silence is complicity with evil, and that the fight for equality was not separate from but indeed at the very heart of Christian discipleship.

King’s letter to my ears strikes a rare and prophetic chord. It is hard-hitting without being mean-spirited. It is incisive without being divisive. It is gracious in its tone even while it sears the soul. It hurts in all the right ways.

And as such, I read it and meditate on it deeply every year on this day. The letter is an annual pilgrimage for me which I take to be a critical part of my own long pilgrimage towards a life of faithfulness to Jesus that is more humble, more just, and–I pray–more healing.

And a long pilgrimage it has been. I did not grow up in a racially diverse community. The city I was born and raised in–Marshfield, Wisconsin–was almost completely white. My mom will sometimes recall the first time I set eyes on a Black person. I was a year old, and we were at the swimming pool. When a little Black girl came up to splash alongside me, “You just froze, and stared,” says my mom.

That about typifies where I came from. You’re not like me, and I don’t really know what to make of you. On the rare occasion that a Black or Latino family showed up in our church or city, their dark skin stood out in stark relief amid the sea of whiteness and–perhaps inevitably, and much to my embarrassment–I would often think, “How did you get here?” with another question not far behind it, “Are you sure you belong here?” When a Black church from Georgia came up to visit our very white church one weekend, grateful as I was to make new friends and experience a culture unlike my own, I do remember feeling a small sigh of relief that next weekend, church would go more or less “back to normal.”

By the grace of God, as the years have gone by, the Spirit has lovingly battered and deconstructed a great deal of that ethnocentrism, often by completely flipping my world upside down. When I went off to college at Oral Roberts University, by random assignment I found myself on a dorm floor that was traditionally (mostly) Black. I was one of four white guys. Two were grandsons of a famous southern televangelist, and one was a lanky track star from Canada. It had the makings of a lonely year.

Yet to my surprise, the brothers on the floor took me in and made me feel like one of their own. I cannot tell you how bizarre that was for me, how it turned my world upside-down. “I’m white. I’m supposed to be welcoming you. And you’re welcoming me?”

And they did. My nextdoor neighbor Brandon quickly became one of my best friends at ORU, constantly giving me a hard time about all the bizarre white stuff I did. An example. I’ll never forget heading off to class one day and having Brandon stop me in the hallway. “Do white mothers not love their children?” he asked. “Well, I can’t speak for all white mothers and since I’m not really sure what you’re getting at…” I mumbled back at him. “Look at yourself,” he said, “shirt and pants all crumpled up like you just pulled them out of the bottom of the laundry basket. You’re gonna go to class like that? Get in here and give me that shirt.”

Which, of course, I did, following Brandon into his room where he pulled out his iron and ironing board, and taught me how to properly starch a shirt: crisp and sharp-looking. It was a revelation to me. I thought we were through. As I gratefully pulled the shirt back over my arms and started to button it up, Brandon looked at me and said, “Pants.” “Excuse me?” I said. “You heard me,” he replied. “Your pants. You can’t go out into society with your pants looking like that. Off with ‘em…”

Once again, I obliged, and there I stood, pants-less in Brandon’s room receiving the de-centering ministry of the Spirit to my white soul via a lesson in ironing.

The whole thing was actually hilarious. A bonding moment that was one of many such moments where community and a genuine sense of brotherhood emerged across ethnic and cultural barriers. I’m really grateful for the experience of that year. It was a first lesson for me in learning that “different” doesn’t mean “dangerous”, that “other” doesn’t mean “wrong” – that we all have much to learn from each other and that, if we’ll allow it, our unique experiences and ways of looking at the world can and should enrich each other.

But there was more in it for me than that. It was also a first lesson in learning that my own upbringing, way of being, and experience was and is not “right” in the sense of being “first” or “primary”–which, by the way, is the very meaning of ethnocentrism. You can be very warm and open to people of other ethnicities, cultures, and experiences–even friends with them–but if you believe that yours is the one around which the others somehow orbit, that yours is the root of which others are branches, that yours is the main plot of which the others are subplots, you’re guilty of ethnocentrism. You might be–but probably aren’t–aware of it, but you are. It is (to wax theological for a moment) a species of that original sin–pride–that needs to be repented of and healed.

My own repentance and healing are still very much underway. The year I spent on that dorm floor at Oral Roberts began the process. I can remember sitting with those guys, listening to them talk about their upbringing in the deep South or L.A. or in the inner city of Chicago, of which often startling and always ubiquitous experiences of racism were an inextricable part, and thinking to myself, “Does that really still happen here? In the same country that I grew up in? I thought the Civil Rights movement happened? I thought racism was behind us…”

I learned then, and am learning now: It does still happen. In this country. Even after MLK and Civil Rights. And though we’ve made significant strides, it’s not behind us.

I know this because the Lord has been kind enough to me to continually grace me with Black and Brown friends who are helping me see the world through their eyes. The stories make my stomach turn. When we lived in Denver, two of our dearest friends were an interracial couple who were graduate students at DU. In the years that we knew them, nearly a half a dozen times, the husband was stopped by police while out on a walk near the university–sometimes in broad daylight. The first time he told me that, my jaw dropped. “You? Here? Why?”

His answer, “Why do you think?” still staggers me. I have never had that happen to me. I probably never will. And neither will my kids. But for our Black and Brown brothers and sisters, both subtle/systemic and also out-and-out forms of racism are still, tragically, daily realities that they have to live with, which ought to break our hearts. Such things should grieve us to the core.

For my own part, I experience grief around it on many fronts. I grieve, first, that it happens at all. When I think about my Black and Brown friends who have been so good to me, in whose faces I have and am continually seeing the face of God, who have known and experienced discrimination and racial violence in their multiple forms, it tears my soul open. It is not the will of the Lord, and it makes me hurt.

What adds to my grief is how many of my white brothers and sisters there are who–it’s nearly unthinkable to me–deny that discrimination and racially-motivated violence still exist. I will be unsparing here. Such a point of view is a heinous denial of reality that can only be sustained by failing to allow the actual experiences of Black and Brown folks to penetrate one’s consciousness. What’s worse is how many religious leaders and talking heads equate caring about racism with “wokeness” and some far-left political agenda–a scare tactic that tragically keeps many from engaging the issue as they ought. Yes–you can engage with the issue in a “woke” way. But that’s not the only way. You can also engage it as an act of discipleship. “Continue to remember those in prison as if you were together with them in prison, and those who are mistreated as if you yourselves were suffering” says the writer of Hebrews (Heb. 13:3). As followers of Jesus, we are called to care about the mistreatment of others because God cares about their mistreatment, and because we are all sharers in the same mortal flesh–the very flesh that Jesus Christ made his own, dignifying beyond all reckoning by his resurrection.

But honestly, I think what grieves me most is how far I still have to go. I’m not saying that because it’s the chic thing to say, but because it is true. Over the years, while I have certainly been shaken by acts of racial violence we have seen in our country, what has shaken me more–God forgive me–is how many times I have not been shaken as I ought. That alarms me. It alarms me how many times I should have spoken out but didn’t. How many times I should have used my agency to lift others but didn’t. How many times I should have stuck my neck out but didn’t.

So often my failures were cloaked with the garb of good intentions. I’m not sure I know enough about this incident to say anything… I don’t want to be controversial… Am I really the person to be a voice for this issue…?

God, forgive me.

That’s one of the reasons why I come back to Dr. King’s words year after year. They’re a goad to me. The Holocaust survivor Elie Weisel once said “The opposite of love isn’t hate; the opposite of love is indifference”–which King also understood, saving his strongest words not for white supremacists or klansmen, but for “white moderates” who in the name of not being controversial failed to act on what they knew was right. Of that “moderate” approach, he wrote:

“The contemporary church is often a weak, ineffectual voice with an uncertain sound. It is so often the arch-supporter of the status quo. Far from being disturbed by the presence of the church, the power structure of the average community is consoled by the church’s silent and often vocal sanction of things as they are…But the judgment of God is upon the church as never before. If the church of today does not recapture the sacrificial spirit of the early church, it will lose its authentic ring, forfeit the loyalty of millions, and be dismissed as an irrelevant social club with no meaning for the twentieth century. I am meeting young people every day whose disappointment with the church has risen to outright disgust.”

He was right. He’s still right. I am a 40 year old white pastor and live with the awareness that if he were living now, I would be the exact target of King’s appeal. My commitment before the Lord and before my Black and Brown brothers and sisters is that so far as it depends on me, his indicting words would not be true of me.

I have a long way to go. I feel it in my bones. I feel it when I am addressing racial matters from the pulpit. The way my throat tightens and my pulse raises and I’ll hear a voice in the back of my head telling me that maybe I should use a different example. I feel it when I’m sitting with white friends who want to deny that racism exists and I struggle to know how to respond. I feel it when I write long posts on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and worry that something I said is going to betray my vast ignorance and make me look foolish.

But I’m trying. I’m trying for my friends. For my ORU dorm mates. For Brandon. And Kelbert. And Patrick. And AD. And Ray. And Ruth. And Barrack. And Ken. And Traci. And Jordan. And Chiantel. And John. And my many other Black and Brown friends who have and are making a quirky white kid from central Wisconsin feel welcome, and helped (and are helping) me see with better eyes.

Amen.