I ran across this article over at the Atlantic this morning, entitled “Lumbersexuality and Its Discontents”, by Willa Brown.

The central premise of the article is that the rise of the so-called “Lumbersexual” in our day is a recapitulation of a social trend that first erupted onto the American scene around the turn of the 19th century, at a time when masculinity (particularly white masculinity) was seen to be in crisis. Along with the image of the cowboy, the image of the lumberjack, unencumbered, close to nature, in full possession of his masculine powers, provided a pyschological escape from what had become a socially disorienting and increasingly stultifying existence for many males. Brown writes:

At the turn of the last century, middle-class white men were, everyone seemed to agree, in crisis. They were effete, anxious, tired, and depressed. Magazines and advice books worried that they had lost their vigor—the industrial economy and urban life demanded too much time inside, too much brain-work. Clerical jobs in dingy offices provided few opportunities for advancement to the ranks of the industrial elite, much less for feats of bravery and daring-do. Men trapped in cities began suffering from neurasthenia, a new disease that skyrocketed to almost epidemic status in the 1880s and 1890s. Neurasthenia was the overtaxing of the nervous system, a sort of male hysteria. Some wealthy and educated urban men suffered from what historian T. J. Jackson Lears called “cultural asphyxiation … a sense that bourgeois existence had become stifling and ‘unreal.’” While women were ordered to bed rest for hysteria, the cure for men seemed to be just the opposite: They had lost their vital force, and they needed it back by getting in touch with their primitive, masculine nature. To do so, they looked westward. [To the lumberjack.]

Brown goes on to argue, however, that the romantic image of the lumberjack as embraced by many such men of that day who had lost their vital force was more an invention of urban journalists and advertisers than it was a reality. Real lumberjacking was a terrifying occupation that paid little, promised little (in the way of self-fulfillment and recovering a sense of one’s virility), and often left the lumberjack himself physically diminished, not enhanced. In other words, the symbol that promised a recovery of true masculinity was empty, as they often are. Brown’s contention is that the reemergence of the lumberjack motif speaks to the same crisis of masculinity (now, I would argue, so much more pronounced and pervasive), and is similarly empty.

What shall we do?

As a pastor to a lot of young men, many of whom (full disclosure: I include myself here–I love me a good flannel) are “lumbersexuals”, I wholeheartedly agree that masculinity is in crisis. At least masculinity (again, particularly white masculinity) as traditionally understood. While there is not time here to get into all the causes of this (nor am I the person qualified to do it), it seems obvious to me that changes in culture and society and the economy have left young men without a coherent path to follow that can provide them with a sense of fulfillment as men. It used to be that the path was clear. In something like this order, the tasks were: find a job, find a wife, find a house, build a family, stay in that life over the long haul, grow up into it as a man, exhaust your powers into that life, and then reap the fruits and bask in the glow of having built up a well-ordered existence.

So much has changed now. Men are not looked as (potential) primary breadwinners, nor the obvious (potential) leaders and builders-up of society. Little is asked of them. Less is demanded or expected. They are permitted to fritter their time away in trivialities, living only for the present as the flow of time passes them by, until one day they wake up as 40 year olds, with little to nothing to show for how they spent their time.

This is a real problem. From my vantage point, in working with young men in their 20s and 30s, it is a problem because at some point, the instincts of the male psyche begin to avenge themselves. I’m not a woman, so I cannot speak for women, but I know that as a man, and for many men that I know, one of the primary psychological drivers is the desire to build something, to make a contribution, to have something to show for who we are and how we spent our time. And there is a point at which when one hasn’t built, hasn’t made a contribution, and has little to nothing to show, that apathy and depression go into hyperdrive and men begin to fritter even more time away in trivialities, becoming at best distracted and dilettante, and at worst destructive and dissipated. No amount of flannel or beard oil can soothe the ache of a male psyche exacting vengeance on the man in question.

This, I think, is where the Body of Christ as a family in the Spirit can help. As a pastor, over the years I have found myself fighting against this crisis of masculinity in the following ways:

1) By refusing to allow the young men I work with to live unexamined lives. Who are you? Why are you here? What are you doing with your time? What do you have in your hand? How do you think your life can count for something greater? These are the questions that all people of faith must ask, and they are particularly urgent questions for young men, since the dissolution of family and social bonds has left many if not most young men without father figures who will lovingly help them cultivate an examined life and with it, a robust sense of self. I almost never sit with young men without finding my way into one or all of these questions. I want to provoke them to the self-possession that is a necessary first step to the realization of one’s potential.

2) By insisting that they exhaust every last bit of their agency in the development of their potential. One guy I was working with–a brilliant young man–told me that the thing in Christianity he most resonated with was Christ’s absolute resignation to the will of God in Gethsemane. At the time, the young man was wrestling with some personal darkness, and so this story had particular appeal. After talking for several more minutes, I said to him, “That is a beautiful bit of the Gospel, and I resonate with it too. But do you know what the difference between you and Christ in Gethsemane is? Christ was out of options. The road had narrowed to a single point. You are not. You have agency left, and can move forward. The time may come where the road narrows for you and you have to give it all up in absolute resignation to the Father, but that time is not now, not today.” Sadly, many young men are in exactly this place. A sense of fatalism has washed over them, and no one living with such a sense will exhaust their agency in the development of their potential. We cannot let them stay there. Romantic as it is, fatalism ultimately destroys.

3) By giving them the resources to become men of great self-discipline. No one ever achieved anything of worth–either in the way of personal development, the development of character, or contribution to family or society–without massive self-discipline. The human mind and heart by themselves are a mess of distraction, and the stereotypical male “wandering eyes” I believe applies not just to the realm of sexuality but to the whole of our existence–like five year old boys, we have a way of flitting about from one thing to the next, never staying committed, never seeing any project through to completion, and thus never having the satisfaction of having committed mind, body, and soul to a single enterprise over time, experiencing that internal “job well done” that makes for a sense of wholeness. There is a stick-to-itiveness that is necessary for personal fulfillment, and we do the young men we work with a great disservice if we do not call them to live in it and help them develop it. This is why at our church we emphasize so heavily the personal and communal disciplines of prayer and worship, solitude and silence, sacrifice and service, for without them, we never become all we were created to be. Young men especially need to hear this.

4) By pushing them to begin to make an immediate contribution to culture and society, even if said contribution does not constitute a “final destination” in terms of what they want to do with their lives. I am referring here most especially to ordinary labor, the kind we all must engage in. The great lie of our society is that we cannot be fulfilled or make a meaningful contribution until we have found our “dream job”, which means that labor done in the “penultimate” moment (that is, whatever we do before we finally get that “dream job”) is either a drudgery or a waste of time. I have found young men to be particularly susceptible to this kind of thinking, with the result that since it is MUCH harder than it ever was to find one’s “dream job” and tends to take MUCH longer to achieve (if it is ever achieved at all), many men live their lives without any real sense of purpose or contribution to a greater cause. What a tragic waste. The opportunity for contribution is RIGHT in front of these young men. And we are Christians, dammit, which means that all that we do we are called to do “to the glory of God” and for the good of others. To fail to seize the opportunities presented to us is a slap in the face of the God who providentially orders our lives for good. And to fail, therefore, to provoke the young men in our lives to seize those opportunities amounts to something like gross negligence. There is no reason why, for instance, the young man working as a barista cannot be encouraged to give himself wholly to his labor, to do it well, to perhaps aspire to some kind of management, and therefore to realize the joy of having had a “domain” that he could keep a loving, careful, and watchful eye over, even if he ultimately moves on to something higher and greater. It is all right there, right now.

5) By helping young men see that even as they are, they can begin investing in others, provoking men younger than themselves to begin to realize their potential. In previous generations, this was built-in for young men, as very early in their lives they began to rear children, which meant that from the outset they were expected to get their business together so that they could help their kids (and in particular, their boys) grow up as responsible adults. Most people aren’t having kids until well into their 30s now, which means that for many, this is a massive psychological gap left unfulfilled. But it need not be. If young men are provoked to begin investing their lives in other young men, the joy of seeing others reach maturity can be realized. And in fact, in my experience, taking such a posture has the effect of helping the giver grow into maturity almost as much (if not more than) the receiver. As a father of four, I can attest: being responsible for rearing my kids (especially to my boys) into maturity has done more to instigate my own maturation process than almost anything else I’ve experienced in the last 9 or so years. It has come to feel to me like some kind of law, written in fabric of the cosmos–that when we give of ourselves in the enterprise of seeing others come to maturity, we mature ourselves. The young men in our lives need to start seeing themselves as potential big brothers and fathers to those coming after them. It will work wonders.

6) And finally, by doing everything I can to encourage young men who feel called to family life to pursue it with all their energy. I know everyone is not called to this, and I never assume it. But to those who are, to those who desire marriage and family, with all the joys and obligations attendant to those callings, I encourage them to get on with it, to pursue it with passion, to find a mate who shares their values and outlook and wants the same things out of life, someone who their souls connect with and brings the best out of them, to take the BIG FRICKING RISK of marrying them (there will always be risk involved), to settle into the normal ebb and flow of a life of love, to bring new life into the world and watch it flourish, and to grow old in that life of love with the wife of their youth. Many young men, I feel, have been conditioned by the idea that they have to have their act totally together before they can get on with this. The result of this horrendous mistake in thinking is that most of them never do. Instead, they serially date, often sleep around, and then sometimes accidentally back their way into marriage and family after inadvertently fathering a child out of their foolishness. Would to God that someone in the church had told them when they were younger that marriage at its best is the cornerstone of a coherent life and not the capstone. Life is full of risks, and this is a big one. But when its done right–in community where there is a presence of loving discernment and careful nurture and support of the relationship–it works, it really does! And when it does, it is so satisfying to those young men, for it takes away all the nervous questions about who will love me and where is “home” for me, and liberates the mind and soul to make ever greater contributions to society and culture.

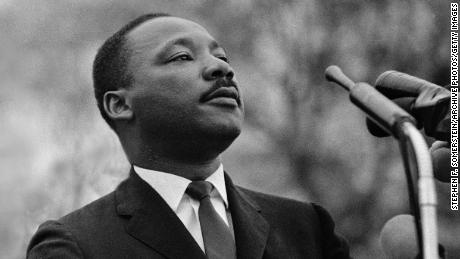

In reality, it seems to me that what we’re talking about here is a masculinity shaped by the person and ethos of Jesus Christ, who was, to use the poignant phrasing of Bonhoeffer, “a man for others.” For too long, the ideal of masculinity has been shaped by “overness.” Those days are gone now, as the changes in society have left fewer and fewer men “over” anyone. But therein lies an opportunity. For as Jesus Christ was not the man “over” others, but the man “under” and “for” others, who both fulfilled and exhausted his agency in the service of others, so it seems to me that our masculinity can be truly realized not by exerting our agency “over” others or by donning empty symbols of masculinity, but when we give ourselves in a fully-developed and full-bodied way to the world that God so desperately loves.

And perhaps wear flannels while doing it 🙂

Grace and peace

Andrew

This is perhaps the first ‘Christian’ article about gender I’ve read that didn’t reek of sexism. Nicely done.

(As a woman I can certainly relate to the need “to build something, to make a contribution, to have something to show for who we are and how we spent our time”, and I vigorously reject the idea that such a problem is relegated to males. But it doesn’t seem that you’re implying that only men feel this way, which is a mistake commonly made in Christian circles. Looking at you, John & Stasi Eldredge.)

Hey Chanelle – thanks for the comment and I agree, I don’t think its relegated peculiarly to males, but as a man I know that if that desire is not met, it wreaks havoc.

Thanks for reading!